Last Friday, I stood with Aya Maasarwe’s father Saeed at the silent vigil and asked him how he is coping with the murder of his daughter.

He told me, a local Palestinian woman, and the group of other Palestinian women I stood with that he is devastated and heartbroken for what happened to Aya, but he does not respond to it with hate. He said that hate begets hate; instead, he responds with prayer and hope for our safety.

That’s what our Islam taught us, he said. That we do not act like the oppressor. That when we do not respond with hate, we can bring an end to these horrific killings.

A New York Times reporter joined us. She interviewed me and a friend of mine, at one point stating: “Aya’s father seems very composed in a time like this.”

I wanted to say yes, he is quite composed. I wanted to say, Don’t you know of Palestinian grief and sorrow? It is our forte. While white men are unhinged over a Gillette ad, Palestinian men’s cheeks are marked with the scars of tears that haven’t stopped falling since 1948. Tears over genocide, settler-attacks, expulsion, home demolitions, imprisonment and now this—rape and murder—where? Clearly not the land of freedom and opportunity, but in a similar oppressive state built on settler colonial, supremacist, patriarchal violence.

But I didn’t tell this white female reporter any of this. She was there to report on the senseless act of male violence against an international female student. The narrative we’re expected to tell is one that affirms white liberal saviour sensibilities: How could we not keep this foreigner safe in our country? We keep silent vigil and promise to do better to ensure such an atrocity does not take place in our beautiful city ever again.

We’re expected to tell a narrative that saves Melbourne from itself; that deflects from the structural violence that enables such crimes and erases settler complicity from the prevalence of male violence. A narrative that sedates people from seeing this crime as a symptom of the white supremacist patriarchal culture of domination that they protect and empower; where aggression, coercion and dehumanisation are the currency in a city built on stolen land.

In contrast to both conservatives and liberals who use crimes like these to expand police powers while neglecting the culture of violence that such responses affirm, and in contrast to zionists and zionist-affiliates who are exploiting this crime to further the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians by misidentifying and claiming Aya’s identity as Israeli, Aya’s father responds with prayer.

He responds by telling me that he doesn’t know what motivated the young man, why this young man decided that Aya must die, so he prays.

As a mother of two boys, I stood next to the grieving father of Aya wishing our world could be safer. It is incomprehensible to me that we live in a society that conditions young men into a toxic hyper-masculinity as a means of gaining power. It makes no sense that someone would even think to rape and murder a young woman on her way home. Why, when she screamed and resisted, could they not just stop? Why can’t men just stop?

Why can’t those who hold power and privilege just stop?

Stop, so that the owners and custodians of this land can take back their power and abolish this version of Australia born of hate, begetting hate.

Aya’s father is only here to take his daughter’s body home to bury her in the land where he is custodian and indigenous, so that she may reside beside the other shuhada [martyrs] in a lineage whose blood has stained the occupied soil.

We said to him, may God accept her as a martyr. She may not have been murdered in Palestine by an oppressive state, but she is the victim of a similar, familiar hate.

A hate which traumatises women across this city and forces them to live in a state of perpetual fear, which brought them over to pay their respects to Aya’s father and join him in his grief, as they grieve their own sense of safety and livelihood marked by violence. A hate which inspired some of them to lay down sunflowers, roses and hand him hand-written poems as they shook his hand and embraced him, unsure of whether they were comforting him, or desperately yearning for his words to comfort them.

A hate which brought a pet bird to sit on his shoulder and whisper to him, in the hope that it eases his heart a little. A hate which still did not prevent him from looking through the flowers to honour the cards laid down by young women in solidarity with Aya.

‘Hate begets hate’ is very apt to this narrative where one Indigenous youth gets caught within the toxic cycle to perpetuate an act of hate, and another Indigenous youth flees hate only for it to catch up to her on another blood-stained land. Saeed provides a transgressive point as his grief for his daughter parallels a grief for an occupied, stolen homeland; filled with sorrow, agony and a desperate hope for us to break out from oppression, to be free from the politics and systems of hate.

Hope that Palestine will one day be free and our young may live long lives away from sniper bullets and tanks. Hope that we can survive and stand steadfast against supremacist violence that is designed to bring out and breed the worst in us before it annihilates us. Hope that we can remain triumphant against the worst of oppressions.

Hope that young men can listen and learn from elders such as Saeed Maasarwe, and turn to their elders here who are praying alongside us within the Palestinian community this week, to keep their children safe from the poison of the politics of domination that continues to destroy the present and future of Aboriginal youth.

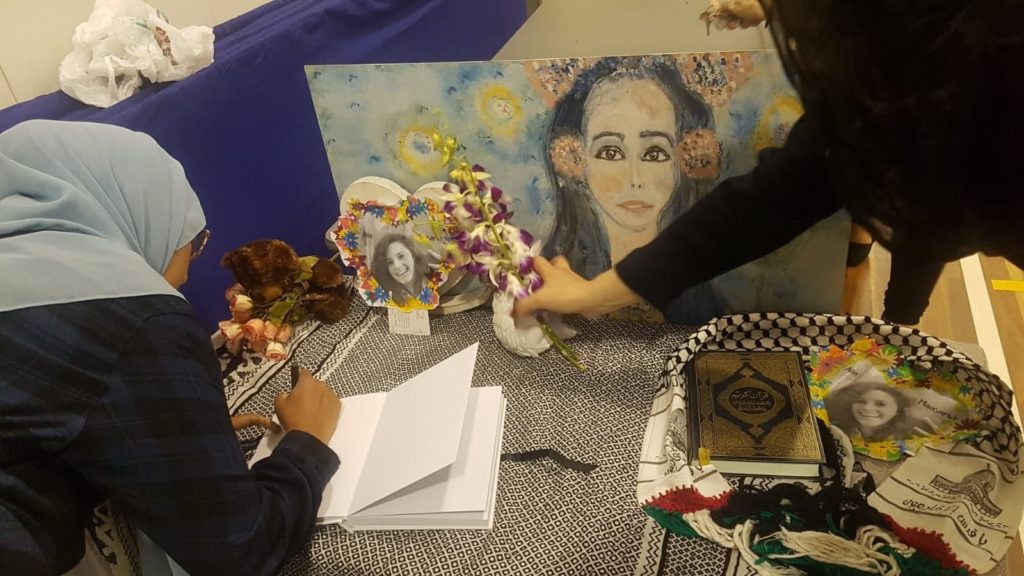

At Aya Maasarwe’s ‘azza [Islamic condolence gathering, similar to a wake], her father repeated much of the same sentiments he expressed at the vigil: that he had raised his daughter to be the next generation of Palestinians who carry love and bring about peace in the world.

As Saeed prepares to farewell this city, my wish is that we can push his message of centring a politics of hope, and let that hope live on.

Cover image via Facebook

About the author

Tasnim Sammak is a PhD student at the Faculty of Education, Monash University (Clayton). She's a spokesperson and founder of Solidarity for Palestine - Narrm, Melb.