Editor’s note: Although written from Hella’s POV, this piece was co-written by Hella and Grace.

♦

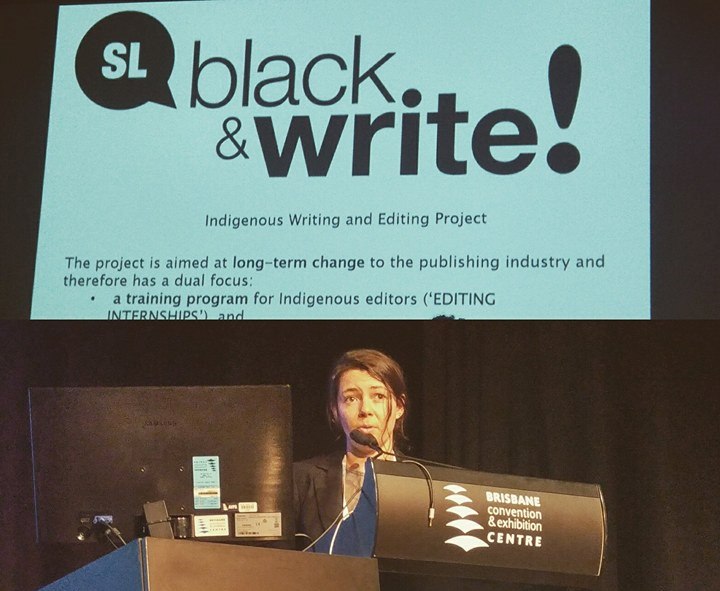

At the 2017 IPEd conference*, there was a session held by black&write! on editing work with Indigenous content. I went and watched as Dr. Sandra Phillips and Grace Lucas-Pennington took the stage and discussed the importance of having an Indigenous editor working on Indigenous content. It occurred to me that in the six years I’ve been studying and working in publishing, I’d never met an Aboriginal editor.

I got Grace’s contact details and met up with her a couple months later to talk about diversity—or rather, the lack thereof—in Australian publishing, and how she got into the industry.

“I’ve always been a massive reader,” she tells me. “Lived in the library as a kid. And I wanted to be a journalist for the longest time, because I thought it was the way to bring truth to people. To tell important stories, to be informed and bring issues to people’s attention. Then I found journalism wasn’t the best way to do that.

“I heard about this entry-level editing internship at black&write!—you basically just had to be interested in books, have some communication skills, be able to write. I applied and was lucky enough to be offered one of the training positions. I never thought I’d work in publishing, ever. Never even considered it as a job. I had no idea how the industry worked or what an editor even did. So it was a massive learning curve. But it turns out I’m pretty good at it.”

She’s not wrong about that. In an interview with Kill Your Darlings, author and poet Alison Whittaker had this to say in response to the question, ‘Did collaboration with an Indigenous editor differ from experiences you’ve had working with non-Indigenous editors?’:

Grace Lucas-Pennington, aside from her great aptitude as a writer in her own right, was both a visionary and a surgeon for my manuscript.

Grace’s edits were about getting the architecture of the collection together in a way that didn’t break meaning. She also enhanced and shaped what was already in the manuscript, including its layers of privy that are coded for Indigenous readers.

That Grace is Bundjalung was fundamental to this process, and also to building a creative relationship of trust and cultural reciprocity.

Both Alison Whittaker and Dr. Sandra Phillips (during the IPEd session) make the point that having an Aboriginal editor working on writing by an Aboriginal person brings a crucial depth to the editing process.

We don’t have any reliable statistics (or any at all as far as I can tell) on the number of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander and other people of colour (POC) writers that are being published. In the piece ‘Diversity, the Stella Count and the whiteness of Australian publishing’, Natalie Kon-yu writes:

I would guess that the Australian publishing industry simply does not publish enough books by women who are not white but there are no figures for this. How many Indigenous writers are published each year? How many non-white writers are published? And what kinds of books are being published?

Part of this lack, I think, comes from constraints placed on writers who are “othered” by the industry. For example, I think that it is probably easier for an Indigenous author to be published if they write about epic struggles, rather than breezy romantic comedy. Likewise, I think that migrant writers will have an easier time getting into print if they follow the well-established trope of the happy, grateful migrant.

Natalie, myself and several others are currently working to get a diversity count of published authors going, but I feel like we’re missing a critical point in all this.

The reasons for not publishing more Indigenous writing are many—and many of the reasons stem from the ongoing effects of genocide and dispossession—but a significant reason is the lack of expertise that mainstream publishers hold around working with Indigenous authors. Australian publishing in general sees ‘Indigenous Writing’† as tricky for various and often overlapping reasons; two commonly stated reasons being “We don’t feel comfortable taking this on”, and “We don’t know any freelance Indigenous editors that could work on this manuscript”.

In short: we need diverse authors, but we need diverse editors too.

The We Need Diverse Books movement originated in the US and has been gaining momentum in Australia as the lack in Australia becomes more recognised. The reasons why we need diverse books seem self-evident to someone like me—a North African child of migrants who to this day struggles to find books that feature Egyptian people who aren’t relics of an Ancient past or corrupt/terrorist/poverty-stricken stereotypes—but if you need a refresher, it’s a subject that’s been written on over and over (and over, and over, and over).

Mainstream editors and publishers often raise questions of appropriate handling of both Indigenous-authored and Indigenous-content manuscripts. I guess it’s good they’re asking. But why has it taken so long to realise that cultural competency is missing from this space?

There is a recognised need for Indigenous and other POC editors in Australia, people who can work with this content competently and comfortably. As the former head of publishing at Magabala, Margaret Whiskin, put it in a 2011 interim report on the black&write! program:

An Indigenous editor can have an understanding of the issues and cultural sensitivities that may be a barrier between a non-Indigenous editor and an Indigenous writer and it can allow for freer communication and a greater trust to be built between editor and writer — there can be a greater familiarity, ease and sense of connection.

Also, there may be subtle changes, unconscious biases that creep in from a non-Indigenous editor, because of their cultural background — an Indigenous editor can have more awareness of some of the stereotypes of character and language.

But where are these editors? Grace tells me there are just three editors she knows of who are Indigenous and working in mainstream fiction editing.

yes, we are a highly diverse company. susan in accounts is a goth

— gay apparel (@figgled) August 1, 2016

I’m no statistician, but I attempted to look into rates of diversity among editors in Australian publishing. According to 2011 ABS statistics, there were 876 book or script editors employed in the literature and print media industry (30.16% increase from 673 in 2006). Of course, this number doesn’t account for the fact that between 2011 and 2015 the number of people around the world using the internet went from 2.21 billion to 3.22 billion. In Australia, 66% of the population had internet access in 2006, 79% in 2011, 85% in 2015—so it’s highly likely the number of online publications has risen exponentially as well. It also doesn’t seem to account for freelancers, and probably doesn’t account for all the new and emerging editors currently not getting paid for their work (of which there are plenty) either.

For the sake of argument (and a lack of any other reliable data) let’s apply that the same rate of increase to the years between 2011-2017; a 30.16% increase on 876 puts the number of editors employed in the industry at about 1140. Let’s assume that’s an accurate number of editorial-types in Australia.

I put a call out across Facebook and Twitter to see how many of that potential 1140 are people who identify as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander or other POC. From that call-out, 32 people identified themselves as currently working in some way as editors. Of 1140. That’s a whopping 2.8%.

Of course my networks aren’t as extensive as I’d like them to be so it’s highly likely there are a bunch more self-identified POC editors out there who didn’t come across the call-out, so let’s triple that number to cover the gap. That’s still only 8.4% POC editors currently working in the industry.

The numbers get even more dire when you look only at Indigenous editors. Of the 32 names that came up, only five—or 0.4%—are Aboriginal people.

We could triple that number—1.3%—heck, let’s sextuple it just for fun and that’s still only 2.6% percent Aboriginal editors in the Australian publishing industry.

(Don’t have faith in my numbers? Don’t worry, neither do I. None of the bodies we’ve applied to for grants want to fund this, and we don’t have sufficient resources to fund it by ourselves. If you believe this research needs to be carried out methodologically please consider donating to the research fund.)

I also put the question to my non-POC editor friends on Facebook. One of them, after telling her I’d yet to find a full-time salaried black editor working in traditional publishing, asked me why I thought that was. There was a suggestion it came down to skill level or qualifications.

But how could that be right? Of the editors of colour who responded to my social media call-out, only two of them didn’t have a tertiary qualification, and all of them had experience. It’s not like black editors and other editors of colour don’t already exist despite a perceived lack of ‘skills’ or qualifications.

Not to mention that even if it were the case that we somehow collectively had lower skill levels than our white counterparts, that kind of response shows a failure to understand the wider institutional, structural and systemic issues that affect us POC disproportionately. There’s a wide range of factors that affect our ability to gain qualifications in this field, like the fact that safe housing, healthcare or consistent education have not been equally available throughout history and access to both is still low for Indigenous peoples and to a lesser degree other POC.

Besides, more often than not, getting a job in this industry comes down to experience over qualifications. Which, again, is harder for First Nations people and other POC to gain.

Black women, for example—this issue disproportionately affects black women thanks to institutionalised racism and sexism and the wage gap—can’t always afford to undertake the unpaid or underpaid internships that have become a requirement in this industry. Nor can they generally afford the 5- to 10-year internship and editorial assistant period it takes to get a wage more than $50, 000 a year. Their families might need them to be earning that wage at age 15 or, y’know, they might have been stolen away from their families and given to a white family and never got paid for their work.

Grace tells me that through the black&write! internship, she and the other editorial interns completed some courses at QUT to upskill on the writing and grammar side of the job, but that it’s mostly been about going straight in and actually working with authors to produce and develop manuscripts. I tell her I think qualifications are generally bullshit anyway.

“And that’s what most people already working in the industry have said to me,” she says. “But it’s also still the first requirement on every single advertised editing role. Must have a degree in… They’ll consider you if you don’t have it, but…”

Still, she says, there’s a niche for Indigenous editors and beta readers for fiction.

“There’s now a demand for people that can a) work in a culturally competent way because publishers want the best possible end product, and b) talk about the issues at writers’ festivals and things like that—race is the hot-button issue of the moment. No-one wants to be the publishing house that’s hit with the next diversity scandal and loses their bestseller or gets boycotted by a group.

“On the flip side, it’s not so much a demand as a need for the authors, for whom working with an Indigenous editor means not having to explain, or worse yet defend, their culture, ideology and history.”

It’s also a need for the audience. The AusCo report Reading the reader: A survey of Australian reading habits found that fiction and non-fiction books by Indigenous authors and books about Indigenous cultures are a small but extremely important component of the Australian publishing scene. Almost two-thirds of Australians (63%), including almost one-third (31%) of non-readers, think books by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander writers are important for Australian culture. This support for Indigenous writing does not fully translate into actual readership; but it’s noteworthy that over 40% of survey respondents indicated that books by Indigenous writers were of interest to them. This data is no doubt affected by the relatively small number of titles by Indigenous authors available in bookshops and libraries compared to the vast numbers of other types of books.

“There’s a demand for these kinds of stories. Publishers can’t say ‘Aboriginal writing doesn’t sell’ anymore, when you look at Claire Coleman’s critically-acclaimed debut novel Terra Nullius (Hachette, 2017) which has had three print runs already—impressive for any debut author.”

I’ve started noticing a fair bit of backlash lately against what I call oh them ethnics misbehaving again; what happens we dare point out the whiteness of the Australian publishing industry, although this phenomenon is, of course, not limited to the publishing industry.

I ask Grace if she’s noticed this backlash.

“The fear response from the majority to the minority, slamming them down for speaking up in places where we previously didn’t, now that there’s enough of us in these spaces to come and speak? And people in the majority aren’t comfortable, and their reaction is fear and pushing away?”

Yeah, she’s noticed.

“200+ years of colonisation and it’s like, we are playing your system now. There are artists and creatives who are speaking up telling the world the way they see it, and saying we don’t have to conform to it.

“This is our culture and our society too, and we have the right to participate in it. And if you don’t like it and won’t move aside to make the space, well. We just won’t do it around you. We’re centring Indigenous—contemporary, real, authentic Indigenous—experiences, whether that’s rural or urban or family-orientated or individual-orientated, or someone that’s really connected to their culture or someone who’s just found out they’re Aboriginal. All real, valid ways of living.”

It’s the erasure that annoys her or makes her really angry, she says. Telling people their reality isn’t valid causes harm. It makes people feel like they don’t belong.

“We’re making noise. We’re not ‘misbehaving’, we’re doing what we want to do. It’s just because they’re afraid and we’re in a space they regard as theirs, or one that we have to have permission to enter. We don’t need their permission. We’re doing it anyway. And that’s what scares them.

“The next generation of writers are building on what came before, and this is my thing, I guess, about the publishing outcome. I think that’s really important. Other things can’t really give you an experience of someone else’s reality like a book can. Maybe I’m the last generation of people who’ll say that.”

In a traditional publishing landscape, editors and publishers are the ones who stand between authors and readers. They decide who they will publish, who to promote, who ‘matters’ and what is ‘relatable’ and ‘readable’.

I tell Grace I think it’s much easier for someone to go into a bookstore and happen across a book where representation happens organically as opposed to being told something like ‘sit here and consume this ten-part series on how fucked the world is’.

“Yep. There’s no empathy connection. It’s less didactic and it’s not like you have to learn this. I guess it can be done, but if you’re going to learn about other cultures, that’s not the best way to do it. That’s just self-evident to me.”

She tells me about educators in higher learning institutions who, when they start talking about the massacres or the policies and everything that’s happened in history to students in the creative writing or education disciplines, find there’re always students, every single year, who turn around and say, “We didn’t know, we weren’t told”.

“That is shocking and horrendous to me. We [black&write!] want to increase representation. And I really believe in the importance of this project and of bringing stories by previously-unheard people to the mainstream by whatever way that we can, to amplify voices that haven’t been amplified for 200+ years.”

There are people who believe there’s sufficient representation of Aboriginal people and other POC in Australian publishing today, though. (Just read the comments section on articles written on the topic.) I ask Grace what she thinks of that. She laughs.

“There’s not. What is sufficient? Do you want parity with the actual population? Do you want parity with the 200-year timeline of ‘Australia’? What do you call sufficient?

“I would say every individual story, if we could reflect that—that would be sufficient. I disagree with [the concept of 3% Indigenous population = 3% Indigenous representation in the industry] entirely because, hello? History? I mean, sure, but then let’s apply that to everything else. 51% women in parliament. 3% Indigenous representation in parliament. Actually, even 3% would be a huge improvement.”

I wonder how much longer it’ll take before something fundamentally shifts in the way the industry works. For editors of colour to be hired and paid to do the work they trained to do, for diverse stories to be ingrained into mainstream publishing without needing separate or special shelf-space.

“I don’t think it’ll take very long,” she says. “But I think it may not be through a bookstore, or through a library, or it may not be in school. I think it’ll be through the internet, possibly, or self-publishing… there are so many ways in, now, to access writing that there wasn’t before.

“I think what you’re talking about is a real culture shift in publishing (as an industry) for that to become equity with the population. And I’m not sure that’ll ever happen because there are too many constraints as a business model for that to be effective. It’ll be really interesting to see what’ll happen in the next ten, twenty years.”

Until then, I suppose, we’ll just keep making noise, entering ‘their’ spaces, and scaring them.

In the excellent film We Don’t Need A Map, academic Ghassan Hage makes a similar point while talking in the context of migration, refugees and asylum seekers: Australians are in constant fear of ‘their’ spaces being stolen.

“You know it can be stolen,” he tells the audience. “Because you did it.”

† There is an important difference between Indigenous-content and Indigenous-authored works.

black&write! makes no attempt to define ‘Indigenous Writing’. Their writing competition accepts Indigenous-authored fiction manuscripts. There are no rules that it must be about Indigenous Australians, or Indigenous issues. They get fantasy novels, horror novels, protest poetry, experimental poetry, detective novels, and everything else.

Although much Aboriginal literature is written in the non-fiction genres, there is a fast-growing pool of fiction writers that explore the realities of Aboriginal experiences in their novels; authors such as Alexis Wright, Tony Birch, Anita Heiss, Kim Scott, Jared Thomas, Nicole Watson, Bruce Pascoe, Melissa Lucashenko and Ellen van Neerven.

*Editor’s note: It should be noted that Hella was at the IPEd conference because her workplace sent her there; she’s not a member of and is not accredited by IPEd, mostly due to the costs associated with membership that she can’t justify on her current salary.