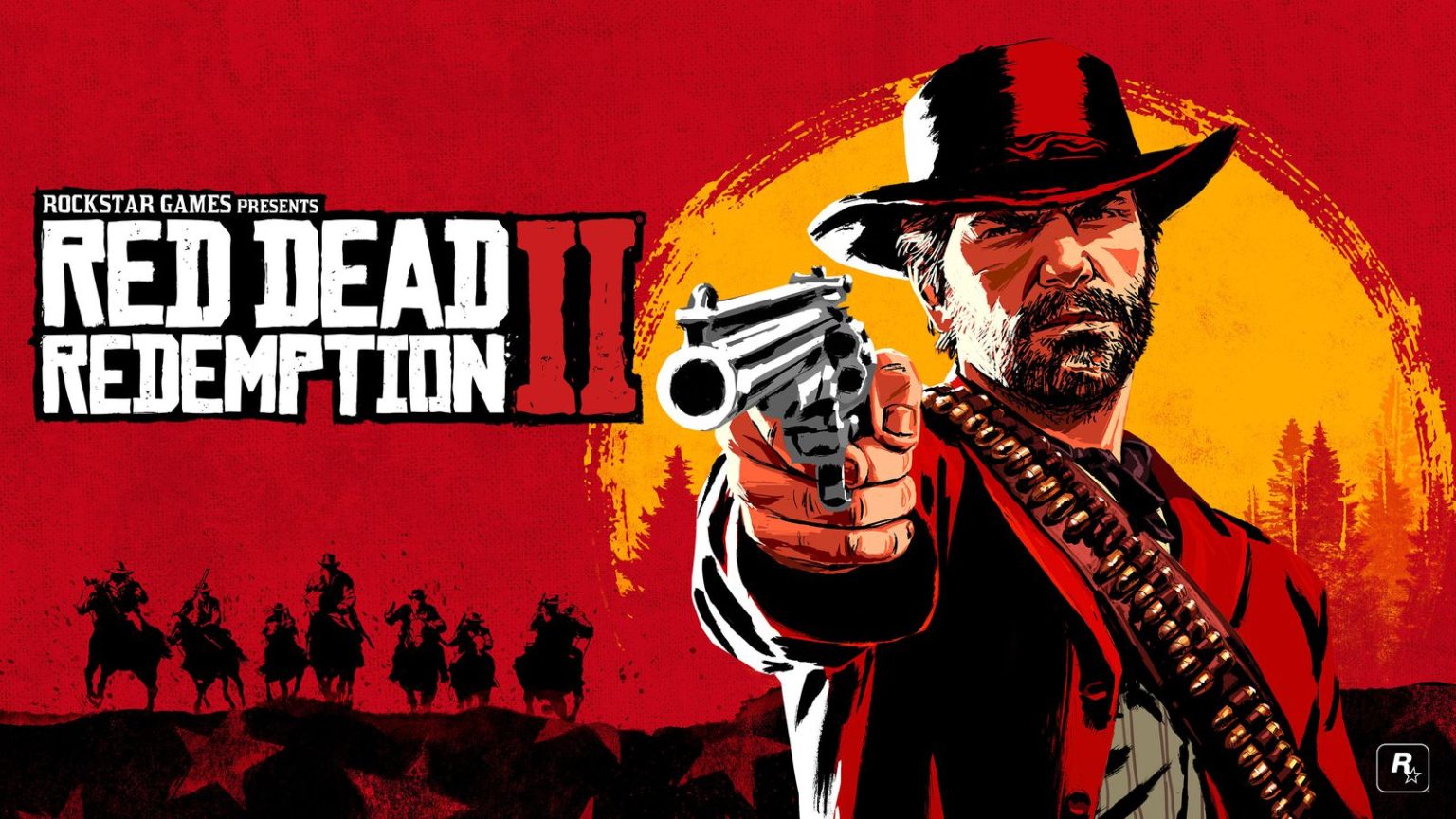

The hit game from Rockstar Games, Red Dead Redemption 2, is a true Western. It explores the end of an era, when outlaw gunslingers are running out of time as colonial governance steadily creeps westward, making their way of life antiquated and irrelevant.

Where once these outlaws had free reign to rob and pillage, now they are hunted by government agents and face up townsfolk who say they’ve chased out rabble rousers worse than you.

Like all Westerns, it is a story of men navigating complex moral codes in a space where law was scarce and might was right.

Red Dead Redemption 2 functions as an allegory for the modern era of #MeToo and an increasingly self-aware society that has had enough of traditional masculinities.

The game focuses on Arthur Morgan, the right-hand man to gang leader Dutch van der Linde, a quixotic Yankee cowboy who wants to lead his small band of twenty outlaws (men, women, and children) out west to “live free”.

Throughout the game, Dutch’s plans become increasingly frustrated by capitalists who own private armies, rival gangs that take up government contracts to hunt you down, state agents who will no longer tolerate lawlessness, and even a shoehorned Italian mobster—because why not.

Dutch starts to lose control over his world. He goes on more and more revenge missions in violation of his own mantra (“Revenge is a luxury we can’t afford”), killing people in cold blood—first enemies, but then innocents. Gradually, Dutch also becomes more and more paranoid, insisting ad nauseam to his followers who begin to lose faith in him that he “has a plan” while his grip on reality seems to slip.

Instead of adapting to changing rules and finding fresh opportunities in the new world, Dutch doubles down on the habits that get him and his gang into trouble.

Arthur becomes disenchanted with the gang as he witnesses Dutch deteriorating. When Arthur is diagnosed with tuberculosis (which he contracted when beating a man to enforce a predatory loan), he begins to reach out to other characters for guidance. He realises that blindly following Dutch and the outlaw way of taking whatever he feels entitled to has robbed him of a better life with his love interest, Mary Linton.

And so, Arthur’s redemption arc begins. He fights to save John Marston, his fellow his gang member turned brother, and John’s family from the outlaw life. Though both men feel conflicted about being disloyal to Dutch, who was a father figure to them, Arthur points out that the leader has not changed with the times.

Dutch van der Linde and Arthur Morgan are ciphers for the choice that men face in 2019.

Thanks to feminism, in its many incarnations, women have been able to interrogate their place in the world. They’ve opened spaces to talk about how stereotypes and gender roles affect them, about how utterly deadly and unjust patriarchy is, and they are taking these conversations into the public sphere.

Men have not done this. In fact, we’ve always relied upon the work of women, and particularly women of colour like bell hooks, to interrogate the effects of traditional masculinity and patriarchy on us.

Meanwhile, the world around us is changing. We’re at the end of an era. Traditionally unquestioned gender roles such as being the breadwinner, or the head of the household are no longer celebrated. “Locker room talk” and casual misogyny are no longer tolerated, at least in public.

Like Dutch and Arthur, men are presented with a choice. Incels, MRAs, and other men who see the changing world as the fault of women, are doubling down on traditional masculinity. Under pressure, and unsure of how to navigate a world they can’t control, they exaggerate traditional ideas of masculinity to the point of toxicity and blame women for their inability to adapt.

Incels and MRAs are increasingly losing their grip on reality.

Instead, we must think for ourselves. Like Arthur, we must learn to navigate the values of this new world, adapt, and grow.

Like Arthur, we will make mistakes. We will routinely disappoint ourselves and others in this endeavour. No one quite knows what gender justice looks like yet, least of all us men who have always sat on the top as hegemons.

As we slowly learn to let go of entitlement, to listen, to shut up, and to not be cowards, we can only be happier as we learn to synergise with a world that is gradually, hopefully, maybe-if-we-keep-working-really-hard-then-maybe-just-maybe becoming more just.

About the author

Saúl A. Zavarce C. is a Melbourne-based Venezuelan-Australian Human Rights advocate who migrated to Australia in 1992. He identifies as a mestizo and gender-queer, with Indigenous, Afro-Venezuelan and European heritage. He is the Head of Advocacy at the Venezuelan Australian Democratic Council and Campaign Officer at Plan International Australia. He holds a Master of International Relations, specialising in gender and radicalisation theory from Monash University.