Recently, we published a piece called ‘Passport pains’. Following publication, we received feedback on it from several sources, and we’d like to take this opportunity to address the concerns that were raised with us.

♦

The piece appeared to reinforce the idea of a single Sri Lankan identity, when in fact Sri Lanka comprises an ethnically, linguistically and religiously diverse population.

There is also the matter of caste systems in Sri Lanka, which includes Sinhalese castes and Sri Lankan Tamil castes. (More on that later in this article.)

All of these factors combined affect how different individuals experience privilege and mobility. This nuance was not present throughout the original article; a lot of what was written was presented as a universal truth, but in fact applies to a specific section of the Sri Lankan population. Other members of the population face ongoing oppression and barriers along class and ethnicity lines both in Sri Lanka and outside of it, including having extremely limited mobility, inability to gain citizenship, access land, claim asylum or escape torture, and that should have been alluded to in the original piece. It was not made clear enough that the Sri Lankan experience is not one-dimensional or universal.

Read also:

Why Ethnicity Matters in Sri Lanka, Sangam

Check Your Sinhala Privilege, via Tumblr

‘Passport pains’ discussed difficulties of going on holiday/traveling for study as a Sri Lankan, but there’s a lot more to the topic than what was covered. It’s impossible for a single article to cover the enormous complexities around mobility and travel for Sri Lankans, and the author acknowledges that while she wrote this piece more as memoir of her personal experiences not as a commentary piece on the state of passport issues throughout the country, these are important concerns, and pushing these conversations into the spotlight is vital.

Freedom of movement is a privilege. We know this. We also know that Sri Lankan Tamils continue to be persecuted in their home country, and that their movements are restricted, and that threats to their safety are ever-present especially with the former president’s recent return to power. Those attempting to flee Sri Lanka to safety are intercepted and arrested with the support of the Australian government. [1]

Read also:

Sri Lanka’s Tamils are at imminent risk after Rajapaksa’s return, Aljazeera

A Long History Of Tamil Persecution, Colombo Telegraph

Statelessness in Australia, Refugee Council of Australia

We also know that Australia plays a part in the ongoing persecution of Sri Lankans. Apart from historically maintaining problematic relationships with Sri Lankan government officials and refusing to back investigations into the country’s war crimes, Australia’s actions around asylum seekers also breach international law.

Both major parties delight in bragging about ‘stopping the boats’, or, more accurately, sending people to death and danger (apparently appeased enough by reassurances that ‘all is forgiven’ by the lately-ousted former Prime Minister). [2]

Our current glorious leader (not for long, hopefully. May election anyone?) has a goddamn boat-shaped trophy boasting the words ‘I Stopped These’ on his desk. Families are being separated and members forcibly deported or held in detention. Boats are being sent back before they reach our shores. Sri Lankan asylum seekers committing suicide after being told they would be forcibly deported back to danger. [3]

Read also:

The Charade of Australian-Sri Lankan Relations, RISE: Refugees, Survivors and Ex-detainees

After the war: why Sri Lankan refugees continue to come to Australia, The Conversation

Among the feedback we received on ‘Passport pains’ was that the choice to publish it as is amidst all this in Australia was politically myopic.

We sincerely apologise. As an Australian publication, it’s important for us at Djed to play our part in holding our government accountable for its appalling track record around these issues. It’s also extremely important to us to raise the voices of those in the diaspora who often find themselves being silenced. We want to provide as safe a space as possible for marginalised people in Australia to write their own narratives and to see themselves reflected accurately on our pages.

Crucially, we also want to stay cognizant of the fact that the term ‘people of colour’, while useful, hemegonises the experiences of the multitudes of people who fall under the umbrella term. There is no single story; there is no single identity; there is no single narrative.

The truth is, neither the editor on this piece nor I picked up on any of these issues prior to being given feedback, and that is entirely due to our own privilege. I’m not Sri Lankan myself, and although the editor on the piece is Sri Lankan, they do not face the same restrictions around movement faced by others.

In trying to learn more on the topic, I was directed to the following Instagram story, which I found really helped my understanding. I’ve transcribed it below and added additional links to further reading in hopes of providing more context around the issue:

Geography by @varathas

“Land protests have been in the headlines for years across Eelam. A large number of these have been in the Vanni and are women-led; Keppapilavu and Pilavukkudiruppu protests are cases in point (Follow recent developments on @tamilguardian).

Read also:

War on the Displaced: Sri Lankan Army and LTTE Abuses against Civilians in the Vanni, Human Rights Watch

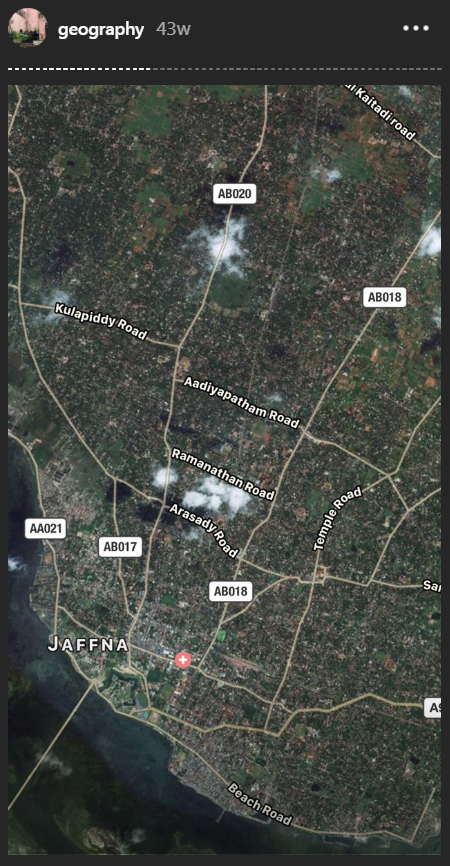

In 2016, the Sri Lankan military occupied over 12,500 acres of private land across Eelam. Tamil-owned land. Much of the land the Sri Lankan army occupies is located in strategic locations. What does that mean?

It means points of interest that enable control over land and people. They are at entry points to cities, towns, villages and islets, at beaches, in the midst of jungles and farmlands and so on. Hardly will you find occupied land in the midst of Tamil town and cities.

Read also:

“Why Can’t We Go Home?”: Military Occupation of Land in Sri Lanka, Human Rights Watch

The Long Shadow of War: The Struggle for Justice in Postwar Sri Lanka, Oakland Institute report

So let’s look into Tamil geographies and spatial orders.

Land distribution and settlement patterns across Eelam are traditionally organised by caste. Land ownership has for centuries been the privilege of Vellalars. Lower and oppressed castes owned none or only, in rare cases, miniscule patches of land. Wealthy Vellalars, on the other hand, owned land beyond their own homes (e.g. many Jaffna Vellalars own/ed farmland in the Vanni). [4]

Land ownership across Eelam was and is clearly a question of caste. But so is the question of where you live.

The spatial designs of Tamil settlements are regulated by caste boundaries i.e. caste as a religious system of segregation and hygiene organises where people are allowed to live and interact with. Thus, where you live or origin from is already an identifier of your caste in Eelam. The closer you live to a kōvil, to a town centre, or schools, the more likely you are going to be of privileged caste background (Vellalar, Chettiyar, Brahmin). Caste creates a system of apartheid that shifts oppressed and lower castes into the outskirts of settlements and often literally into jungles.

By segregating people, upper-castes attempt to retain their “purity” rules and the privileges it affords them. Retaining purity levels is a collective project that all Vellalars are involved in as a way of keeping their collective status. Which means that when a Vellalar wants to sell land in a Vellalar settlement area to a non-vellalar, this causes trouble, outcry and policing.

So how does this relate to the question of occupied Tamil land by the Sri Lankan army?

Strategic positions that are of higher interest to the Sri Lankan state for its colonial project are mostly at the outskirts of towns, islets, in jungles and in seaside areas. They form entry points and infrastructural access points that allow for surveillance of land, people, and their (im)mobility. Hence they overlap with more likelihood with spaces that are home to oppressed and lower castes than those reserved for upper castes, which effectively also means that more people who struggle for land releases from the Sri Lankan army and end to long term displacement are of oppressed and lower-caste origin.

Read also:

Tension over army ‘seizure’ of Sri Lanka Jaffna land, BBC News

Acquisition Notices: Militarization Through Grabbing Of Tamil Lands, Colombo Telegraph

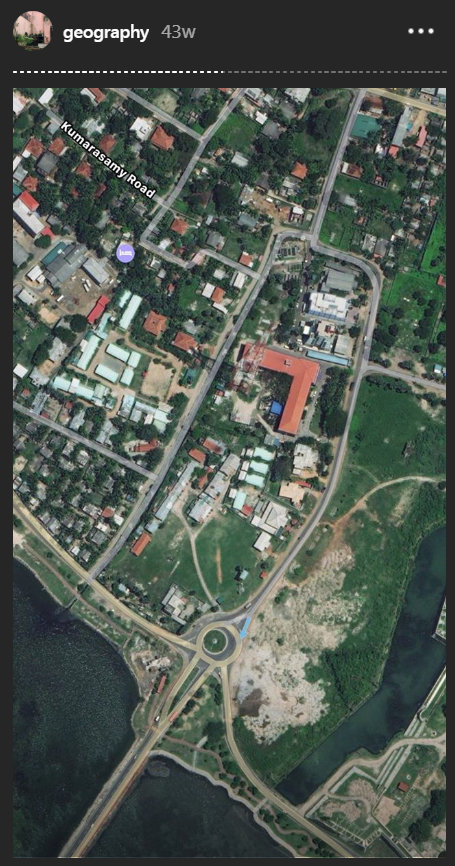

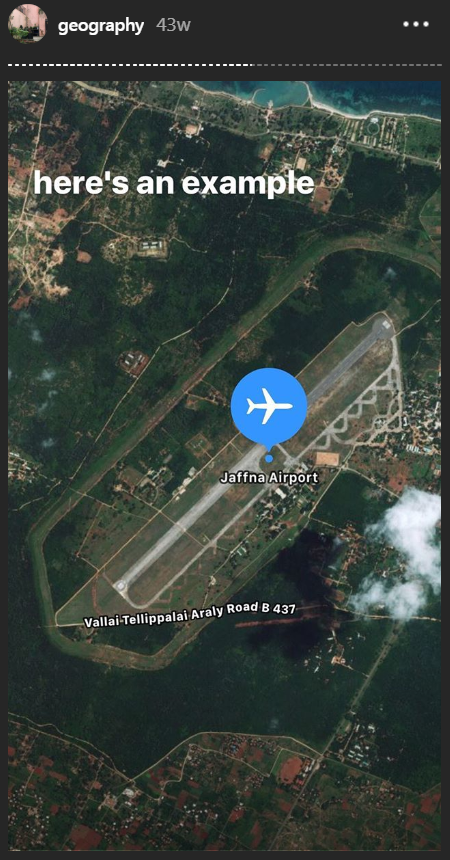

Here’s an example:

Palaly airport and its surroundings in Jaffna have been occupied by the Sri Lankan army since 1976 to combat the Tamil independence movement and limit Tamil autonomous movements. Much of Palaly airport’s bordering population has over the years been displaced as a result.

The most detrimentally affected were people of oppressed castes, specifically the Nallavar caste, of whom thousands remain displaced after decades of occupation. To date, decades later, they remain displaced residents of refugee camps in Jaffna. In fact, almost all long-term displaced Tamils who reside in refugee camps across Eelam are oppressed caste members. [5]

The question should therefore not just remain a critique of the occupation of the Tamil homeland by the Sri Lankan state but also extend to a critique that’s more inwards directed, towards a Tamil societal order. Oppressed castes are not just prevented from returning to their lands by the Sri Lankan state, but also denied access to the Vellalar-dominated property market across Eelam which leaves with little options but to remain refugee camp residents.

Read also:

Bittersweet return for Sri Lanka’s displaced Tamils, UCA News

Sri Lanka announces limited freedom for detained Tamil refugees, The Guardian

What if a Vellalar agree to sale of land to a non-Vellalar?

If a Vellalar decides to sell land to a non-Vellalar, it usually leads to an exorbitant price hike that renders it unaffordable and/or the seller will be blamed for bringing caste shame upon his people.

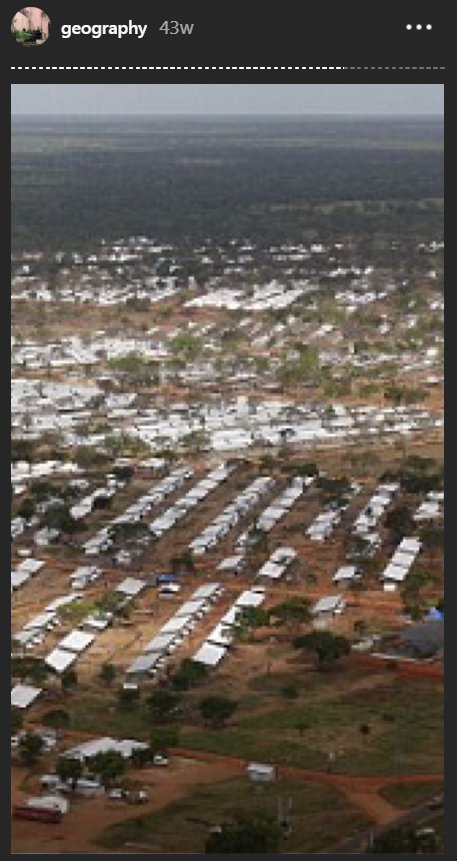

Remember Menik farm?

Menik farm was a concentration camp built by Sri Lanka for more than 290,000 Tamil genocide survivors. The camp near Vavuniya was notorious for it many rights abuses, including disappearances, systemic rape, torture and murders by the Sri Lankan army. The detainee numbers of the camp shrunk over time, until the concentration camp was finally closed in 2012. [6]

Read also:

Sri Lanka’s Menik Farm refugee camp ‘to close’, BBC News

Menik Farm: The tragic end of a bitter saga, from detention to forced relocation, GroundViews

The first Tamil detainees to be able to leave Menik farm were detainees with foreign passports, wealthy ones and others with capital and mobility. Both capital and mobility are highly informed by caste, which means the more capital you were able to mobilise, the shorter your stay in the detention camp.

Which effectively also meant that oppressed caste members were left the longest in the concentration camps.

Some of the last detainees of the camp were so desperate that they wished to stay longer in the camp beyond its closure because:

- the Sri Lankan army occupied their homes

- their homes were destroyed in the war

- they had no money to buy new land and little opportunities to live elsewhere because of caste apartheid.

This situation reflects back on how land disputes continue to affect oppressed castes across Eelam and how land protests in Eelam always sit at the intersection of anti-Tamil racism by Sri Lanka and caste discrimination by upper-class Tamils.

Without cast analysis, there is no analysis.”

See also this Instagram story by @varathas for some modern Tamil history context.

[1] [expand title=”Read more: Tamils facing new atrocities in Sri Lanka“] “Many Tamils have returned home after the war to discover that their land had been stolen. Indeed, Tamil NGOs report a ‘Sinhala colonisation’, of predominantly Tamil areas. A Tamil refugee told Amnesty: ‘My brother went back to check on his property and found that nearly 100 percent of our areas are still under Sinhalese military occupation’.

Years after the supposed end of the civil war, allegations of torture in police custody persist. UN human rights commissioner Navi Pillay warned in 2013 that Sri Lanka was becoming increasingly authoritarian. Tamils face the risk of sexual violence, torture, murder, imprisonment, and enforced disappearance. Juan Méndez, UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, concurs.

Since March 2014 Sri Lankan authorities have intensified security operations in Tamil areas. There have been scores of arrests and several deaths in these regions and freedom of movement has been restricted in these areas. According to an estimate by The Sentinel Project, ‘the overall risk of genocide in Sri Lanka is medium to high’, as ‘conditions point to a likely renewal of conflict in Sri Lanka that could escalate to mass atrocities including genocide’.”

Tamils facing new atrocities in Sri Lanka, Eureka Street

[/expand]

[2] [expand title=”Read more – Australia’s obsession with ‘stopping the boats’ “] “Australia did not vote in favour of this resolution, which was a change in approach. In the two previous UN Human Rights council resolutions Australia supported moves to encourage Sri Lanka to investigate allegations of war crimes. The change in the Australian position is because the Australian government wants to bribe the Sri Lankan government to stop allowing asylum seekers from leaving by boat. The Australian government’s simplistic obsession with stopping the boats means it is prepared to overlook the history of persecution of Tamils, and the serious allegations of war crimes, torture, and continuing widespread human rights abuses. This is morally repugnant.”

Why Tamils flee Sri Lanka, Eureka Street

[/expand]

[3] [expand title=”Read more: Preliminary findings of the visit to Sri Lanka“] “Through exceptional provisions that admit the use of uncorroborated confessions made to police officers as the sole basis for convictions, it has fostered the endemic and systematic use of torture. Entire communities have been stigmatised and targeted for harassment and arbitrary arrest and detention, and any person suspected of association, however indirect, with the LTTE remains at immediate risk of detention and torture.

The Special Rapporteur is encouraged by the Government’s recent adoption of a ‘zero tolerance policy’ towards to the use of torture; and by the appointment in July 2016 of a Committee to Eradicate Torture by the Police. In Sri Lanka, however, such practices are very deeply ingrained in the security sector and all of the evidence points to the conclusion that the use of torture has been, and remains today, endemic and routine, for those arrested and detained on national security grounds. Since the authorities use this legislation disproportionately against members of the Tamil community, it is this community that has borne the brunt of the State’s well-oiled torture apparatus.”

Preliminary findings of the visit to Sri Lanka, United Nations OHCHR

[/expand]

[4] [expand title=”Read more: Dealing with caste prejudice and inequalities in Sri Lanka“]

“Even more than in South India, Brahmans are numerically weak and economically inferior to the Vellalars in Jaffna and elsewhere in Sri Lanka. Pfaffenberger suggests that the South Indian caste system evolved through cooperation between Brahmans and Vellalars. The Vellalars conceded the pre-eminence of Brahmans in the caste hierarchy and in turn the Brahmans accepted the wealthy land owning Vellalars as next in line, fit to own land and to manage temples in which Brahmans functioned. The scales were tilted towards the Vellalars even more in Jaffna than in South India reflecting the reality of the numerical and economic marginalization of Brahmans in Jaffna.”

Dealing with caste prejudice and inequalities in Sri Lanka, The Island

[/expand]

[5] [expand title=”Read more: Casteless or Caste Blind? Changing Patterns of Caste Discrimination in Sri Lanka“]

“However, there is some evidence that among those remaining in IDP camps in certain parts of Jaffna peninsula, certain Pancharmar caste groups are prominent. Thanges (2006), for instance, found that in three IDP camps in Mallakam Nalavar, Pallar and Parayar were predominant. Most of them had been displaced from high security zones established by the military in 1990s. It appears that the Sri Lankan military prevented the return of these IDPs to their original lands by the continuation of high security zones.

On the other hand, they have not been able to move out of IDP camps due to land scarcity in Jaffna, lack of employment opportunities and possible difficulties in purchasing land due to poverty and hesitation on the part of higher castes land owners to sell land to the Panchamars due to the fear of intermingling with them.

While these IDP camps receive basic amenities from the state and NGOs, they remain isolated from the neighbouring communities and have sometimes experienced difficulties in utilizing public amenities such as schooling for their children, drinking water from public wells and entry to local temples controlled by upper castes (Thanges 2006, Human Right Watch quoted in Goonesekere 2001, Vegujanan & Ravana 1988).

This seems as an important feature of sustained caste-based discrimination in Jaffna society in spite of widespread and more or less irreversible changes noted earlier. Reactivation of caste-based discrimination in disaster situations has been reported in Gujarat earth quake and other disasters in South Asia as well (Goonesekere 2001, Gill 2007).”

Casteless or Caste Blind? Changing Patterns of Caste Discrimination in Sri Lanka, Indian Institute of Dalit Studies (IIDS)

[/expand]

[6] [expand title=”Read more: Crimes Against Humanity in Sri Lanka’s Northern Province“]

“In the early months of May 2009, in Mullaitivu, the entire population of close to 300,000 persons including civilian men, women and children who were trapped in LTTE-controlled territory and escaped the fighting were detained and subsequently interned in a cluster of camps. While the largest batch of IDPs emerged from the ‘no fire zones’ in May, many had crossed over to government held territory earlier were already placed in internment camps. The largest of these camps was Menik Farm in Vavuniya, where approximately 250,000 individuals were held. The military was in control of the camps and internees were not allowed to leave. The access of aid-workers, human rights groups, independent journalists and opposition politicians to the camp was heavily restricted. Many families were separated for months in different camps, without knowledge of the fate of the others. The detention of the inmates of the camps had no known legal basis. None was offered.”

Crimes Against Humanity in Sri Lanka’s Northern Province, Sri Lanka Campaign for Peace and Justice report

[/expand]

About the author

Hella Ibrahim is the founder and editorial director of Djed Press.