The one and only time I saw myself represented on the school reading list was also the one and only time I didn’t finish reading an assigned book.

I was a top student who devoured everything on the booklist before the school year started. So why, when a Chinese protagonist featured on the syllabus for the first time in my 13 years of schooling, couldn’t I get past the first few chapters?

Maybe it’s because I felt embarrassed whenever classmates would point to the Chinese girl on the book cover and ask if she was me. Or maybe it was the fact that this book, set in Ancient China, was written by a white person and I could tell when parts weren’t authentic. Some of the dialogue sounded like it was from a fortune cookie quote, for goodness sake!

I couldn’t stop cringing when the characters spoke broken English. I remember reading sentences like ‘Don’t touch stone’ or ‘You no longer slave. Free. Travel to ocean’ and thinking Yeah, nah, not gonna finish this. I found the use of broken English profoundly unsettling; that’s how strangers—at the park or at the checkout counter—would mock my parents…

But this isn’t an evaluation of whether a white woman should have been writing about a Chinese girl; others have written about this topic better than I ever could. This is about how I felt when I first encountered representations of Asians that resonated deeply with me.

One high school lunch time, I was waiting for a teacher in the English staffroom. My eyes naturally gravitated towards the nearest bookshelf: there was the requisite Shakespeare, some Jane Austen, and some Fitzgerald. But one particular title caught my eye: Growing Up Asian in Australia, an anthology edited by Alice Pung. An excited whimper involuntarily escaped me.

“Everything okay?” a concerned teacher asked.

“Yeah, it’s just—it’s just… I can’t believe it! There’s actually a book about Asians who grew up in Australia! That’s me!”

The teacher, visibly taken aback by my enthusiasm, nodded and walked away. Now, you might think that my overexcitement was too much but the year was 2009, way before Benjamin Law’s television series The Family Law hit our screens in 2016, way before Ronny Chieng: International Student came out in 2017. I borrowed Growing Up Asian in Australia from my local library that same day.

I remember feeling butterflies because this was the first time that I ever saw my life reflected on a book’s pages. Alice Pung wrote about how she had to translate letters for her mother because the only literature her mother ever consumed was the weekly Coles catalogues. I wanted to weep knowing that someone, somewhere, had had the exact same experiences as me.

Benjamin Law recounted how he and his siblings would speak loudly in their strong Aussie accents at Gold Coast theme parks, in an effort to distinguish themselves from the Asian tourists. I laughed so hard at this—I thought it was only my family who did that!

From then on, I chased that magical feeling of being understood by seeking out work from other Asian-Australian writers. Alice Pung, Benjamin Law, Michelle Law… they just got me when no one else did.

So you can imagine my absolute delight—nine years after first reading Growing Up Asian in Australia—when Michelle Law’s Single Asian Female hit the stage.

“Look, there’s a play about me!” I’d tell my friends.

Single Asian Female introduces us to Mei, who like many high school students feels pressure to conform. But for Mei, fitting in means erasing her Asianness; it means becoming white. Mei goes on a purge: her glasses—which reinforce her status as a stereotypical Asian nerd—have to go. So too does her Doraemon and Hello Kitty paraphernalia.

Like Mei, I went through this “wanting to be white” phase in primary school. To this day, I feel so ashamed that I avoided and ignored my Chinese teacher whenever he spoke Mandarin to me in the playground.

“What did he want?” my white friends would ask when Mr Lee gave up and walked away. “I dunno, do I?” I’d say flippantly, pretending to not understand my mother tongue.

Back then, I didn’t know what assimilating meant. 12-year-old me wasn’t trying to be white—I was just trying to be cool, which meant being the same as everyone else.

I lived in a really racist suburb in Melbourne. Being the only Asian kid (apart from my siblings) in primary school was not fun. So when my family moved to Brisbane, I was excited to be surrounded by all these Asians. Kids who looked like me!

But then I decided I only wanted to hang out with the white kids. I was buoyed by their acceptance of me. With their approval, I became super confident. They didn’t have any identity-related insecurities because… well, they’re white and don’t get teased for being so. I absorbed their confidence and strutted around school like I was the best. Surrounding myself with white kids made me feel good about myself.

I still remember my dad’s silent disappointment during a car ride home one day when I said, proudly, “Oh, I don’t have many Asian friends! I just don’t like hanging out with them.”

Luckily, I got over wanting to be white in primary school. It was too tiring and I just couldn’t keep it up. In fact, by the time I got to high school, I despised other Asians for trying to be white because they reminded me of how I used to be the same.

Once, after badminton training, I was walking with my doubles partner to maths class. A friend (who was also Asian) crossed our path and said to my partner: “Oh my god! You look so Asian right now, your badminton racquet’s sticking outta your bag!”

In a panic, my badminton partner stopped in the middle of a busy walkway and hastily shoved her racquet back into her grey Country Road bag. As if concealing her badminton racquet would make her any less Asian!

Going back to Single Asian Female: we also meet Zoe, a 29-year-old single Asian female. There’s a montage of all the terrible dates she’s been on. I watched this scene squawking and violently nudging my friend because, word for word, I’d had the exact same interactions.

“What type of Asian are you?” Zoe is asked by one of her dates.

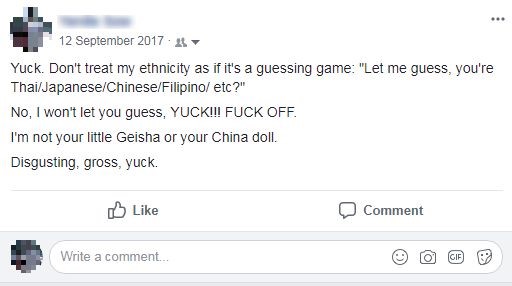

Just last year I wrote an angry Facebook rant about this:

I’d recently started a new job. A white man sitting in the cubicle behind me struck up conversation and asked where my name was from. It wasn’t the only time; he’d always randomly make reference to my Asianness and I’d always feel really uncomfortable during these interactions.

After I was moved to another part of the office, this same white man asked me out via work email. I was still a student, and he was a lot older, so I was disgusted that he would even consider me in a romantic sense. I was disgusted that he would suggest going to the beach or to a restaurant after just a few conversations that mostly revolved around my race.

I complained about how inappropriate this was to a colleague.

“Yeah, he probably wants to put you in a kimono and make you pour him tea,” my colleague said, after I ranted about how much I hate being fetishised and having my race treated as a guessing game.

Single Asian Female was everything to me. Whilst Alice Pung’s Growing Up Asian in Australia reflected my past and childhood, Single Asian Female reflects my present, what I’m going through right now. Reading stuff that I can really relate to makes me feel less lonely; as if the authors in Growing Up Asian in Australia and the characters in Single Asian Female are extending their hands out from beyond the pages to pat my shoulder comfortingly, saying, “I know what it’s like.”

Cover image by benedix/Shutterstock

About the author

Yenaissance is a Melbourne-born Chinese writer, currently based in Sydney. Her special talents include quoting the Star Wars prequels verbatim, and an unhealthy ability to find out everything about her dates before she actually meets them in person. Although she's never won an award for her exceptional online research skills, she was a winner in the 2017 Premier’s Multicultural Media Awards for her writing.

1 Comment

Dear Yenaissance,

My friend Shu-Ling Chua, a Melbourne writer, sent me a link to your beautiful essay here. I loved reading about how you discovered GUAIA in high school and were so excited about it! The book is now 11 years old and still going strong – thank you for reading it and for writing about how much it meant to you then.

Best regards,

Alice

P.S. Ben and Michelle Law rock. 🙂