He runs his hand along the old Huon pine table, searching for the familiar, comforting notch on its side. It’s a faint notch, easy to miss if you don’t pass your finger along the wood. Most people don’t notice it hidden among the indentations and grease stains from years of abuse. They would be too busy admiring the table itself, easily the finest piece of furniture in the house, with its mesmeric, turbulent swirls of wood grain. It reminds him of the deathly tannin-stained eddies of the Franklin River.

“Choy, where are you? Come bring some wood for me!”

Ma yells from the living room, jolting him from his thoughts.

It’s the tail end of summer, much too warm for wood fires. Despite spending forty years in suburban Hobart, Ma hasn’t gotten used to the temperature. Nor to the idea of puffer jackets or woollen jumpers, God’s gifts to Tasmania. She strides around the house with the wood fire at full blast wearing nothing more than a t-shirt and pants as if she were back home in Malaysia.

Or at least, she used to stride around the house, always filled with purpose and menace. He’d become attuned to the sounds the floorboards made in different parts of the house so he could try to pre-empt her path and avoid it. He could remember his apprehension when he used to hear the floorboards creaking closer to his room, praying that Ma would be going next door to Chin’s room instead. By age ten he stopped believing in God. It’s strange to see Ma now, betrayed by her arthritic left knee, the pain slowly but surely triumphing against her sense of purpose.

His hand leaves the Huon pine as he heads to the basement where the firewood is stored. He finds the room completely devoid of firewood. Jesus, Ma. It’s not even autumn. He makes his way back, steadying himself to head out to the woodshed to split some wood.

“Choy, where’s Arlie? Ask her come have dinner tonight. I’m making roast duck, she sure like one.”

“I think she’s at a play Ma, but I’ll ask her.”

He doesn’t have the heart to tell her that things with Arlie ended four weeks ago. After three years of zen-like patience and tolerance Arlie’s facade had come crashing down in a pool of tears. She just couldn’t see a future together, she’d said.

He had tried explaining, for the umpteenth time, that Ma didn’t actually dislike her – that it was just Ma, she would say the exact same thing to any girl he brought home. That her skirt was too short. Or that her top was too revealing. Or that she spent too much money. He was pretty sure the straw that broke the camel’s back was when she’d overheard Ma saying, “Choy, you have to be careful of them guai los – they are just different.” When they made love for the last time it was vicious, desperate and lingering. He couldn’t stave off the inevitable sense of defeat as he came.

On their second date, they had gone to the Don, a good place for a rowdy Friday night and a brave choice for a mixed-race couple. Arlie had cornered him against the wall. They’d been yarning on about his family and Arlie listened, entranced, as he described Ma. In a strange way, he was pretty sure the reason he got laid that night was because of Arlie’s fascination with the exoticness of Ma. In one swift motion Arlie had somehow disarmed him of his glass, and with her left hand on his waist she reached up to his face with her right one.

He flinched.

It was a small, subtle movement, starting with the firm shutting of his eyes, the turning of his cheek, and the final bracing for contact. Always on the left side as Ma’s right hand made contact.

“You don’t have to flinch with me.”

She whispered it in his ear. That was followed by the firm, gentle touch of her lips against his left cheek, in the exact spot where Ma’s ring finger used to strike. He had woken up the next afternoon to the warm hazel gaze of Arlie’s eyes, hungover and hard. The sex had been eager, brief and utterly satisfactory.

Over the next three years Ma would somehow wade her way into the conversation between them at infrequent yet regular intervals. Arlie was fascinated with Ma. She would ask all sorts of questions in the most polite way possible, never directly. He wouldn’t answer her questions in the daytime, when his resolve was strong and his mind was clear. He would masterfully steer the conversation away into the safe realms of university life or the reliably unpredictable Tasmanian weather. It was in the long nights, when he woke up drenched in sweat, sobbing uncontrollably, that his resolve deserted him completely. That was when he would talk about Ma, Arlie holding him tightly and listening intently as they watched the dark stillness turn into the feeble glow of the sunrise over the Derwent River.

“You should talk to her about the past,” Arlie said.

To Arlie, family was everything. She shared every inch of her life with her parents, right down to her sex life. He could never shake the sensation of awkwardness when he shared breakfast with her parents, knowing that only six inches of Gyprock separated their ears from Arlie’s orgasms the night before. Her parents always gave him a knowing, encouraging smile over a steaming Dilmah’s Double Strength as he struggled for coherence on two hours sleep. He wondered if Ma ever had an orgasm. If she did she would probably disapprove.

“It’s been so long ago now, I’m sure she wouldn’t mind. She might even apologise.” Arlie said.

It was a great idea. It had been a long time since he was smaller than Ma. And Ma had softened with age, in direct correlation with the progression of her arthritis. She had been proud of his life and career. She had even taken to Arlie in her own way, though she never expressed any of that openly. She would always be faintly disapproving of any relationship, particularly with guai los, who she thought spent all their time drunk and doing unspeakably dirty sex acts.

Looking back, he isn’t really sure what he had wanted out of talking to Ma about the past. A subtle, light-hearted dig at Ma, or a grudging acknowledgement perhaps. He didn’t expect an apology, but he did wonder if she would.

He picked what he thought was a good moment to bring it up.

“No Choy, you must have imagined that. You were very young.” Ma had said, eyes downcast.

Chin told him later that he went berserk then, screaming at Ma, trashing the living room with tears running down his face. He can’t recall the events himself.

Apparently, he started methodically in a clockwise fashion, starting with the Yamaha piano that had been specially shipped from overseas in a futile attempt to nurture his musical instincts. He had applied a never-used driving iron with an axeman’s precision; the Yamaha played its last crescendo. He moved on to the television, a clunky antique from the ’80s that his family had remained steadfastly loyal to in spite of the meteoric rise of flatter and wider screens. Next was the trophy cabinet, where with tremendous accuracy he managed to launch his Year 6 chess trophy into the kitchen window. Finally he moved on to his medical degree, the centrepiece of the living room, framed in the finest Blackwood looking down on all the visitors in his house. He took considerable time and care with its destruction, smashing the frame before tearing up his degree and throwing it into the wood heater.

Then he left, closing the door gently behind him.

When he returned home the next evening with intractable nausea and stains of whiskey down his shirt, he could smell the faintly pungent scent of sambal wafting out through the broken kitchen window. He walked into the house to find his degree framed up on the wall, as if it had never left. His Year 6 chess trophy was back in the cupboard, behind his International Mathematics Olympiad medal. His driving iron was in the golf bag, where it would lie for the next century unused. Where the TV used to be was now a vase, filled with freshly picked petunias from the Turner’s yard, most likely without their permission.

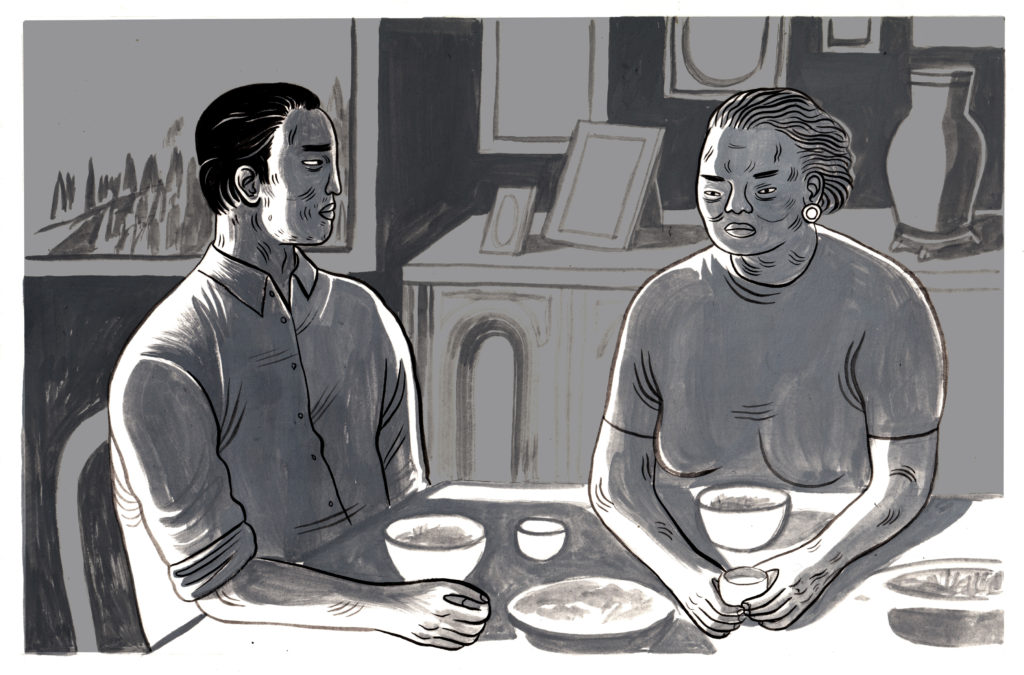

Dinner that night had been a silent affair, everyone looking down into their bowls as they silently shoved food in their mouths. He had sat there, quietly savouring the taste of the sambal tofu – Ma’s apology, perhaps. The silence was occasionally broken by Ma’s urgings to eat more, and his own sullen replies. The quiet clatter of chopsticks against porcelain accentuated the stillness.

Perhaps Ma was right, he’d thought. He had been young and with age his memory had become imperfect – his recollections had been proven wrong before. He could barely remember what he had done at work the day before, let alone childhood memories from twenty-odd years ago. It had been so long ago that memories blended into fiction, the way dreams blend into reality in the early hours of waking. Perhaps he was wrong.

But then he noticed the notch in the wood, right next to where he had picked up his chopsticks. It was no wider than a paperclip, so subtle he had missed it all these years. And the memories came flooding back, right there on the dinner table as his tofu hung in mid-air.

It was two weeks before his Year 6 mathematics exam. There was a particularly difficult probability problem he could not get his head around, and Ma had lost patience with him. She picked up the nearest thing she could hit him with, which that day happened to be a foot-long metal ruler. He had hidden everything else – the clothes hangers, the spatulas, even the shoe horn. But he had forgotten the ruler.

He had raced her around the table, terror giving him a strange gift of speed and nimbleness. But she was in her prime, pre-arthritis, and he waited for the inevitable as she closed in for the kill. With the last throw of the dice he ducked under the table. He closed his eyes and braced for contact.

And then – nothing. He’d opened his eyes to see the ruler lodged in the table, making minimal headway into the steadfast Huon pine.

He had never considered himself a victim. Things like that didn’t happen in leafy Sandy Bay – it was confined to places like Bridgewater or Chigwell, to people who were meant to be pitied and helped. Growing up he thought it was just a fact of life. He’d taken a strange pride in showing off his scars to his closest friends. It defined his ten-year-old sense of masculinity and made him popular with the girls.

He’d brought up the Year 6 maths exam incident in casual conversation with Arlie on the drive back from a week-long ordeal bushwalking on Federation Peak. The Bureau of Meteorology had been overly optimistic, and he had been overly naive, underestimating the wildness of South-West Tasmania. He’d been vulnerable then, the freezing rains driven on by the Roaring Forties whittling down his strength. He’d felt so close to Arlie. When they arrived back at the car, dishevelled and smelling faintly of shit, an incredible lightness washed over him. She drove, and the warmth of the heater and the security of the dirt roads moved him to speak more freely than he ever had. He answered Arlie’s questions with disarming honesty, and Arlie probed further, spurred on by his openness. It wasn’t until he’d regained sensation in his toes that he became aware of the language Arlie was using. It was the very same he had used when he was speaking to a rape victim in the Emergency Department the week before.

“Eh Choy you coming or not? Go get some wood please!”

Ma’s commanding voice cuts through the kitchen wall, piercing his ears. “Jesus Ma, I’m on my way!”

He resurfaces from his memories to find himself back in the dining room. Through the kitchen door he can see Ma fussing about, preparing the duck for dinner. It strikes him that this woman in the kitchen barely resembles Ma. As she moves around the kitchen she subtly shifts her body to her right to keep the weight off her bad knee. She had forgotten to turn on the oven and hadn’t defrosted the duck the night before. In spite of her efforts she can’t mask the tremor in her hands, and she spills soy sauce over the kitchen bench. The inevitable decline of age is etched across her face, the sharpness of her thirties replaced by advancing fragility. She’s shrunken over the years, leaving behind wrinkles of skin that hang lifelessly from her limbs. She is stooping, even bent. She reminds him of the patients he sees in nursing homes – enfeebled, infirm with a tinge of senility.

She doesn’t look like Ma. Too small, too frail. Almost harmless.

He picks up the dining room table, made of the best Huon pine, and heads outside for the axe.

Guai lo: Cantonese term used to describe those of a Caucasian background. Literally means ‘ghost man’.

About the author

Yee Zhao Feng lives in Geelong, Australia. He can usually be found in his backyard tending to his chooks and zucchini plants. He is of Malaysian Chinese origin and fell in love with Tasmania when he moved there ten years ago, where people still yelled things like Fuck Off Back to China (Ya Cunt). His other work can be found in Vertical Life, Verity La and Scum Mag. You can follow him at on Twitter.