It’s almost midnight and eighteen-year-old Yasmine Mustapha* is wide awake. She sits against her bed’s headboard, gazing intently at her mobile phone. The open chat messenger vibrates dully under the blanket. Speech bubbles and emoticons litter the screen. English text interspersed with numerals reads like a secret code. Their secret code.

That is how, four years later, Yasmine remembers her nightly conversations with her future husband. She smiles now as she recalls that memory. I ask her about the “secret code” that she and Sami*, her husband, used to communicate with online.

“It’s Arabic,” she says. “We typed in Arabic using English letters and numbers.”

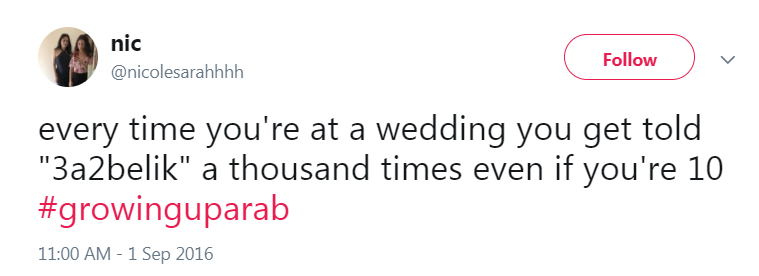

Of course, this ‘code’ is hardly exclusive to Yasmine and her husband. It can be seen all over the internet and especially on Arabic-language pages. It’s commonly known by its users as ‘Arabic chat alphabet’. Other names include ‘Latin Arabic’, ‘3arabizi’, and ‘Arabish’—terms that reflect the hybrid nature of this on-screen dialect. This is because it is a marrying of the Latin alphabet and (funnily enough) the Hindu-Arabic numerals used in English to form Arabic-language sounds.

The rise of Arabish follows a somewhat unconventional route; Arabish is hardly what most would define as a traditional language. Its existence, while unintentional, largely owes itself to globalising forces in the Middle East. One of those forces includes the widespread uptake of technology in the 21st century.

The Middle East’s most widely-used language is Arabic—a language that contains 28 letters in its alphabet. Unlike English, it is written from the right to the left. Yet, the first computers introduced to the region only consisted of English script keyboards. This, of course, posed significant problems to the Arabic-speaking majority. How does one communicate online if the required tools only cater to a one specific but not-applicable language?

In effect, Arabish was a simple language born out of necessity. Over time, it has crystallised into a codified dialect, one used by (mostly young) internet natives living in the Middle East and overseas.

Yasmine tells me she did not have much difficulty learning Arabish code. She acquired the skill after a trip to Lebanon, where she met Sami. He spoke and wrote English at a basic level; her written Arabic was limited. Their desire to keep in touch with one another compelled Yasmine to familiarise herself with Arabish.

“Sami taught me Arabic chat alphabet in my last week in Lebanon,” she says. “It’s a bit technical at first but you get the hang of it after you know which letter or number to use.”

Most Arabic sounds are easy to work out but some can prove to be difficult. Letters like the guttural ‘kha’ (seventh letter in the Arabic alphabet) are not easy to translate using English script. Users of Arabish have overcome this obstacle by transposing these letters onto the numerals used in written English. Here, numbers are chosen according to how stylistically similar they are to the Arabic letter. The ‘kha’, for example, shares similar physical features with the Hindu-Arabic numeral ‘5’. So, this becomes the letter’s Arabish equivalent, like so:

| ﺥ | 5 |

| Arabic letter ‘kha’ | Arabish equivalent |

| خلاص | 5alas |

| Arabic word for ‘enough/stop’ | Arabish equivalent |

Useful as Arabish is, it also has its detractors. Since Arabish is native to the internet, a common sentiment among Arabish’s older-generation detractors is that it is damaging Arabic proper. The fear is that millennial’s high use of Arabish will soon trickle down into Arabic educational systems and most likely result in a ‘dumbing down’ of traditional Arabic—something that, in their view, will surely guarantee the language’s gradual demise.

I asked Yasmine if she believes Arabish to be a threat to Arabic. Her answer is a resounding ‘No’. She tells me that to use Arabic chat alphabet, you need to first have a solid understanding of traditional Arabic. In fact, Yasmine is of the opinion that Arabish has strengthened Arabic, particularly over the internet. This hybrid code has provided Arabic speakers the opportunity to navigate a virtual space dominated by English-speakers. It has also reinforced Arabic as a globalising language, one that can transcend boundaries no matter what alphabet it uses.

Prominent Australian linguist and current head of the Chair of Linguistics at Monash University, Professor Kate Burridge, says it’s simply expected of languages to evolve over time; change has always been a crucial component of languages. Arabic is not exempt from this rule.

In fact, Arabish is the ultimate linguistic product of its period—a bastardised offspring of 21st century technology, traditional Arabic and massive globalisation.

Interestingly, along with older-generation Arabs, second and third-generation Arab-Australians also tend to view Arabish with distaste. The common charge levelled against it is often rooted in Eurocentric superiority, one that racialises Arabish as a ‘fob language’ (i.e. a language spoken by people “fresh off the boat”). Of course, what one could glean from this derogatory description is that native Middle Easterners who try to speak English online are antiquated beings dressing up their gruff language in a sordid mask of modernity. It is either this explanation, or one could go all Freudian and equate the denigration of Arabish with Arab-Australians wanting to be seen as unquestionably Western—that they only speak English.

It’s hard to judge whether Arabic chat alphabet is a negative or positive phenomenon. It may still be too early to tell. What we know for sure is that Arabish has made digital communication much easier for Arabic speakers. It also stands as a testament to our resourcefulness. We can make do with less, and we can make do well – even when all we have is letters and numbers.

*Yasmine and Sami are real people but these are not their real names.

About the author

Ayche Allouche immigrated to Australia when she was a month old. By birth, she is a first-generation immigrant, but was raised with the mindset of a second-generation Lebanese-Australian. Not that it really matters. She has a Bachelor’s degree in Media & Communications and Islamic Studies from Melbourne University. Currently, she is undertaking an Honours year in Islamic Studies, with her thesis focusing on gendered Islamophobia. She doesn’t know what she wants to be when she grows up.