Yassmin Abdel-Magied is under attack for what she represents. She challenges and subverts the hyper-feminine and submissive Muslim woman trope. Yes, the hate campaign against her is undoubtedly Islamophobic, but that’s exactly how Islamophobia works against Muslim women – it confines them to the oppressed Muslim woman trope that can only be escaped through hyper-sexualisation and fetishisation of ‘liberated’ Muslim women (another trope).

Society would have Muslim women believe that they can only fit into one of these two dehumanising categories, so any effort to exercise a different projection of the self is immediately punished.

I wonder, is the self-sacrificial solo social warrior effort worth it, after what we’ve witnessed in Yassmin’s case? Do we need brown women to be Superwoman rather than working as part of a collective in order to progress as people of colour?

In response to the latest media backlash against her, Yassmin Abdel-Magied this week wrote in the preface to an essay in the Guardian: “Many, post-Anzac, said the response wasn’t about me but about what I represent. Whether or not that is true, it has affected my life, deeply and personally”.

The article, titled What are they so afraid of? I’m just a young brown Muslim woman speaking my mind asserts that what she has experienced in the past few months is nothing short of a witch hunt; a vindictive, personal and coordinated effort by the most powerful forces in society to hurt and undermine her – and erase her voice – because of who she is, not what she has particularly said or done.

Watching this unfold as a fellow ‘young brown Muslim woman’, I struggle to comprehend what it is exactly that powerful forces in Australian society, from media personnel to politicians, detest about Yassmin Abdel-Magied – especially since I know many other young brown Muslim women who say more radical things, and participate in more politically radical activities.

Why have they not received the kind of backlash that Yassmin has, and why have their tweets and speeches not been picked up by national and international major media corporations? What is particularly intimidating about Yassmin to right-wing commentators and neo-Nazi groups? Could it be her personal brand that has put her in the spotlight, her body and voice offered as a sacrifice to the cause?

As anyone who has been watching the rise of ‘Muslim activists’ in Western political spheres would have observed, it has become obvious to me that Yassmin Abdel-Magied and others, like Linda Sarsour, are facing very similar, very personal threatening hate campaigns against them. These campaigns are determined to bully them out of the public political space, to push them into disappearance and invisibility, and force them back into the submissive Muslim women trope.

What cannot be overlooked is the similar persona that both Linda and Yassmin publicly embody. One an ‘unapologetic’ Brooklynite (think unapologetic think Linda) who is American Palestinian and Muslim, and the other ‘a 25-year-old Muslim engineering chick’, described as ‘fiesty’ in news headlines. The personal brands which served them has, in a way, been the biggest threat working against them.

They are attacked not only because they are very visibly ‘non-oppressed’, but because they also challenge the objectification and sexualisation of Muslim women. They are not just pretty faces seeking acceptance through a familiar femininity. They are not seeking empowerment by selling a friendly narrative that utilises the feminine to flirt with power.

They are not responding to the hate against them by donating money for every trolling tweet (a gracious act from Susan Carland that has been widely celebrated by many media outlets). Oh how hidden Islamophobes love a story about a Muslim woman’s kind, flower-giving, intimate-cafe-conversing gestures.

Instead, their carefully crafted social media posts and statements are filled with power symbols and power poses.

What Islamophobes quite obviously detest is a Muslim woman who fights back, hits back and stirs even more controversy by publicly refusing to tone down her rage, or sarcasm (i.e. Yassmin on Instagram; Linda subverting the word jihad to mean dissent is greatest form of patriotism).

Yassmin raising her voice on QandA and then being asked by the moderator to tone it down was a perfect illustration of the kind of disciplining Muslim women are too used to, the kind of respectability that Muslim women are expected to pander to if they wish to have any public presence at all. ‘Shouting at each other is not going to help’, Tony says, equating a bigoted, accountable senator with a young woman trying to defend her citizenship rights.

In response to Tony, Yassmin intelligently deflected the embarrassment of a white man telling a young brown woman who is being bullied on live TV to calm down by saying half-intently ‘I apologise for yelling because that is unbecoming – of a lady’. No matter our profession or accomplishments, Muslim women are often reduced to and defined by our gender – rewarded and punished for the way in which we abide by white patriarchal standards.

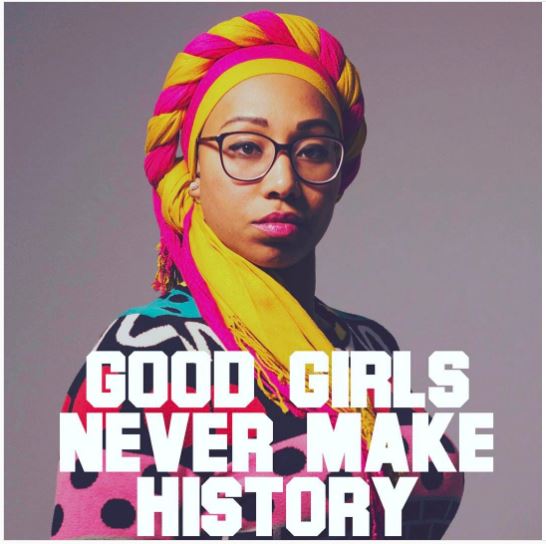

From her bold eye-glasses frames to the colourful large prints and corporate mismatched suits she often models, Yassmin often challenges white supremacy through her image more than through what she actually writes, says or does; an image that is now becoming unacceptable as she moves from being identified as youth to woman. Her political ideologies are actually quite liberal – but that does not give her any bonus points to the judgement of the powerful elite. The image of her ‘two-finger salute’ on the cover of The Daily Telegraph is evidence that non-submissive displays are in and of themselves implications of guilt.

The articles written against Yassmin are filled with exuberant images of her – recontextualising positive, euphoric and youthful smiles to associate her with ‘un-Australian’ values. Yassmin’s extroversion and photogenic qualities are under trial, for a Muslim woman cannot be seen in command of the same values that white males are consistently rewarded for in the workforce.

Her social media presence very clearly follows social entrepreneurship guides that are supposed to teach young people how to break through in a neo-liberal economy where culture is commodified. Maybe no one taught Yassmin that these guides are for white youth only – you, young brown Muslim woman, ought to shrink yourself. And that is exactly what critical theorists have warned about neo-liberalism; it claims to provide equal choice and opportunity, while excluding groups of individuals who do not possess the right capital.

It’s really disillusioning to see that as soon as a Muslim woman ‘activist’ emerges (though Yassmin is not a political activist but more a social commentator – gasp, imagine if she was actually a political activist), her life is literally threatened and no one really can grant her safety beyond precautions.

As a fellow ‘young brown Muslim woman’, I learn that I should not put myself, as a personality, on the line for any cause because the risks are not worth it. Because that is not the path to challenging injustice.

I think many Muslim women today believe that if they gain celebrity status, through vlogging, becoming public commentators, writing memoirs (like Yassmin’s Story or MuslimGirl founder Amani Al-Khatahtbeh’s Muslim Girl: a Coming of Age), becoming the face of anti-racism and anti-Islamophobia work (like Linda Sarsour), the voices of the Muslim women as a collective will somehow be amplified and the causes they are dedicated to will be advanced. If it does, it doesn’t happen automatically. It is not a given.

We have already been taught through the experiences of Black American celebrities (see: Colin Kaepernick, countless others) and through the varied experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (see: Miranda Tapsell, Adam Goodes, countless others) that even as a celebrity, you cannot wield much political power, because the moment you do, you are crucified. Yes, you can go up the chain, but those at the top can topple you all the way down when they feel you’ve stepped out of line.

I admire the courage of emerging Muslim women activists, but I wonder, is it worth the backlash given that both wider and Muslim communities are weary of having to come to their defense over and over again every time the white patriarchal society decides these individuals need to be taken down a peg?

It is not like Muslim communities haven’t been very critical of both Yassmin and Linda; they have. Some within the Muslim communities have been and continue to be critical of Yassmin and Linda for their non-adherence to the stricter hijab representations, and for some of their compromising political stances. I just think, if our own communities cannot see beyond image, as well, and will leave these women to suffer without much support because they made political mistakes, then why should we be throwing ourselves out to the wolves without anyone to back us up?

I understand that there is no going back once you are on the hate agenda, but for other emerging young brown Muslim women, we really need to have this conversation.

I feel that if we work together to promote a collective brand through movements rather than individual personal brands we would be more powerful – and more protected. It’s a conflicting thought for me, because I support every woman’s right to her own name – just as the brown Muslim man Hasan Minhaj deserves a very public platform, so do brown Muslim women – but at the same time, I see that it is individual Muslim women who are being most viciously punished for subverting gender tropes, for what they represent.

Why do women need to keep sacrificing themselves, their autonomy, their careers and their plans for the sake of their communities? Women without the position or status get crucified, while the rest of our Muslim community watches.

Is there a way to hold a public role and avoid solo activism? These are decisions that we need to be talking about as Muslim brown women – because the path of those like Linda and Yassmin is very lonely and increasingly unsafe.

If we are going to lead movements, then this shouldn’t be at the expense of our brightest and most talented women as individuals. It’s too great a cost to gain over the backs of young brown Muslim women.

Cover image © Yassmin Abdel-Magied, via Instagram

About the author

Tasnim Sammak is a PhD student at the Faculty of Education, Monash University (Clayton). She's a spokesperson and founder of Solidarity for Palestine - Narrm, Melb.