There has been a long tradition in the arts and journalism circles of unpaid internships, or asking people who are just starting out to work (or provide their work) for free. If and when questioned, the answer usually comes in the form of a claim that this unpaid work will provide the prospective intern with ‘exposure’ – an exposure that they should only be so lucky to have.

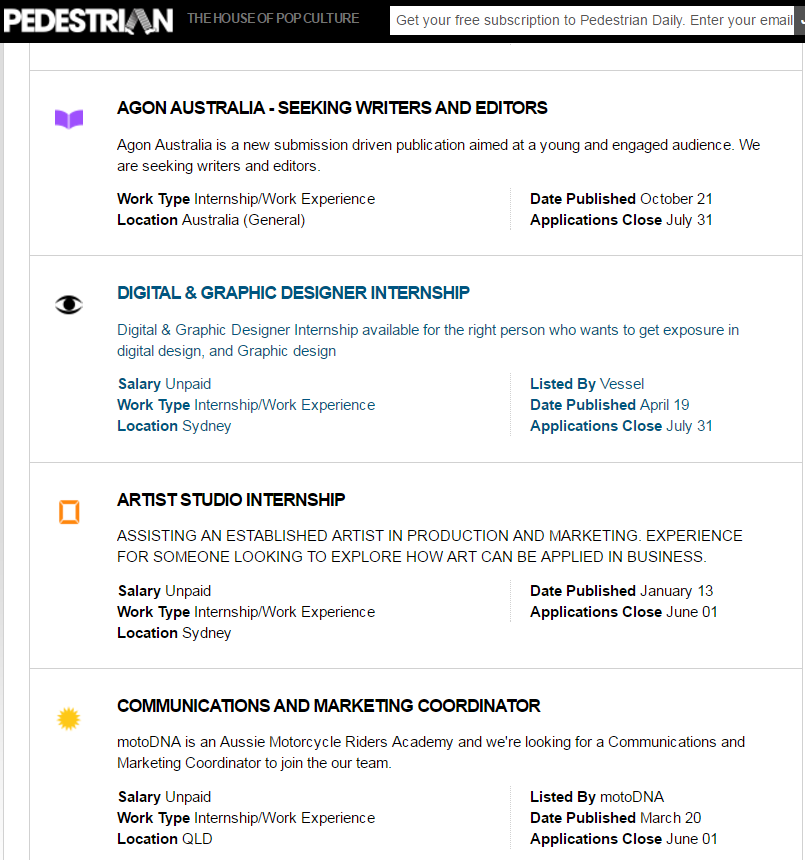

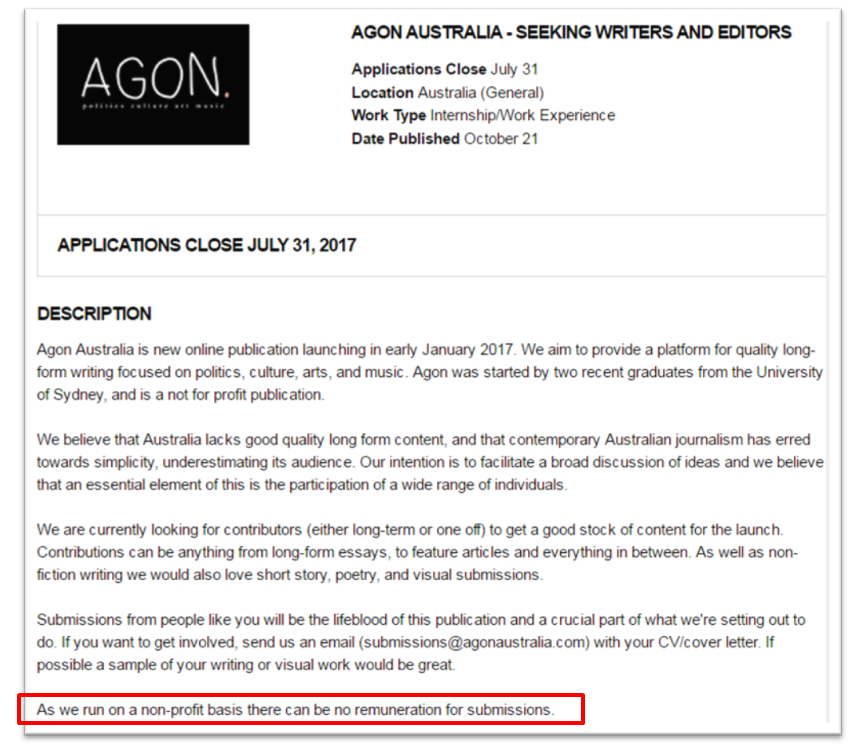

It’s even been used in job advertisements, usually something to the tune of “we cannot offer payment for *insert job here* but for *these reasons* it will be a good way for you to expand your portfolio and gain exposure”.

This exposure may come in the form of getting your work ‘out there’, possibly meeting the right people who might kickstart your career, or simply an exposure to the ins and outs of a particular industry, which might help you get a paying job. Sure, exposure is great, but it doesn’t pay the bills. And I can’t think of any other industry in which this would be acceptable.

Whether we like it or not, we live in a capitalist society. That means, at the end of the day, money reigns supreme. Money not only provides you with a place to live, food to eat, and wi-fi – it can also give you a tremendous amount of access. Access to the right people: people who might know someone, who might know someone else. Access to the right places, so you can get your work in front of the people who ‘matter’. Money dictates who is allowed to speak and who will have to work ten times harder to have their voices heard.

Money can, very literally, change your place in the world.

This issue of exchanging exposure (instead of money) for work stretches far beyond interns. Freelancer writers and artists, who are basically independent contractors, quite often have issues getting paid. I once waited three months for an invoice worth hundreds of dollars to be paid. When I hired some movers to shift all of my stuff from one apartment to another, I paid them pretty much straight away. Can you imagine what would have happened if I waited three months to pay them? Or, alternatively, if I’d refused to pay them and said I’d write a blog post about them instead and tell all my friends about them in the name of ‘exposure’?

Probably because it has worked in the past, and it still works in the present, to a certain extent. It’s gotten to the point where some advertised unpaid internships are little more than glorified administration positions. If no one complains about something that is clearly exploitative, the power remains with the exploiters. There is no reason to change – and why would you, if you could get work for free?

It’s ridiculous. And yet, in the arts, this time-honoured tradition persists.

There may be some who disagree with me, but I believe the advent of the internet has made it easier for larger companies or businesses with a larger reach to exploit interns, or writers and artists who are just starting out. The ability to work remotely – from a different city, or even a country on the other side of the world, means less face time with the person or people you are working for. Very simply, this might make it easier to ignore invoices, to just take work and run. The exposure these businesses claim to be able to offer is far wider and deeper than ever before, and having that particular ‘name’ attached to your work will help to distinguish it from the sea of blogs and Tumblrs and social medias and other, lesser publications that populate internet. And sometimes, the gloss of opportunity is enough to forsake payment in cold hard cash.

Unpaid internships and the ability to produce unpaid work for a publication also bring up an important conversation around class and privilege. People from well-off or otherwise privileged families are more likely to be able to afford to do an unpaid internship, because there is no pressure to juggle a full-time or paying job alongside the hours and labour required for an internship.

This creates a knock-on effect in that these people will be considered more hireable because they are seen to have the ‘experience’ and ‘exposure’ that gets you ahead in these industries. And when they get those jobs, the cycle continues. No wonder – they’ve never known anything different. Again, money rules the world, and people from marginalised backgrounds get left further and further behind.

So aside from the fact that we need money to survive, why should artists get paid? Very basically: writing, drawing, singing – creating something, no matter what it is, takes time. Art doesn’t just suddenly appear out of thin air and float onto your desk or into your computer, ready to be sent off (though sometimes I wish it worked that way). The more complex the piece, the more time it will probably take. And guess what? We deserve to be compensated for that time. Similarly, people from marginalised backgrounds make significant emotional investments in order to tell their stories, or to educate others. They deserve to be compensated for that too.

At the end of the day, art makes the world go round. It is important, and so is paying the people who make this art happen. We’ve all had enough fucking exposure.

About the author

Yen-Rong is a Brisbane-based writer, and is of Malaysian-Chinese descent. She is the founder and editor in chief of Pencilled In, a magazine dedicated to showcasing the work of young Asian Australian artists. When she is not writing, you might find her on Twitter @inexorablist, drinking tea, or chasing after her cat, Autumn. Her website is here: http://www.inexorablist.com.