Growing up I didn’t ever hear or know the word ‘privilege’. It was only used in the context of “it’s a privilege to know you”, as a flatterer’s phrase and nothing more.

I remember as ’90s kids in Auckland, we used to talk about ‘posh’ people. We knew we weren’t one of them. We knew they wore fancier clothes and owned the toys that we saw on the advertisements but never actually possessed ourselves. We knew they spoke more articulately, went to elite sport clubs, knew the rules to all the sports and other games. We knew we weren’t them, but I guess we didn’t give ourselves a label. We weren’t those ‘posh’ kids, so who were we?

I lived in Jordan for two years and was so immersed in a completely different culture that I forgot my place in those small-town New Zealand primary schools. In Jordan, I didn’t belong to any ‘superior’ group, but I began to understand my social position as Palestinian in a Jordanian country. While many of my friends say that their social status is elevated and they feel they ‘belong’ when visiting their migrant-country of origin, I’ve never experienced a sense of belonging to a ‘superior’ group and the status that is afforded to this belonging.

Coming to Australia after Jordan, social division became very evident to me in the way that the girls at the girls’ school I attended hardly built bridges between peer groups. As an outsider, I could see the groups in this very ethnically-diverse school were built around ethnic and religious lines.

For the first year in that school I fluctuated between these groups, belonging to all yet belonging to none. I shared the academic values of the Asian students, the enthusiasm for class participation of the white students, the strict religious upbringing of the Muslim African students, and the second-language of Arab students. I didn’t see it that way at the time, but looking back this is how I understood my status as a new migrant student whose privilege was having university graduates for both parents, a rare capital for Muslim-Arab youth in the early 2000s.

After moving to an Islamic school, I quickly learnt that the students came from very different homes to mine. Parents were either white-collar and emphasised assimilation into Australian values, or blue-collar and wanted a firm religious foundation for their children. I was in the middle. My parents raised me and my siblings with middle-class and Islamic values, yet we didn’t have the middle-class status symbols that the other white-collar students identified with.

Still, I never really knew my parent’s education was a form of privilege. I’ve since come to realise, through doing a degree in Education, the emphasis that is placed on parents’ educational background as a marker of children’s educational success.

At some point it became very clear to me that in order to succeed I needed to compete academically with those ‘posh’ kids I met as a child, the ones who attended the grammar school across the way from mine. I didn’t have access to the resources or networks or privilege they had, but I believed I could achieve just as well. I believed in hard work. The Islamic school teachers taught us that hard work can get you anywhere. They didn’t shame us when we couldn’t pronounce the English names of characters in the set texts. They didn’t belittle us when we didn’t know what ANZAC Day was. They taught us that though we were migrant children with large language and cultural gaps, it wasn’t a shameful thing to be. But when we all graduated and moved to university classrooms, our disparity became very obvious to me.

I was the only female student from my school who went to Monash Clayton, and probably only the second Muslim I knew in my Arts course. Lecturers would make cultural references that just went right above my head. I achieved a score of 48/50 in VCE English but I had no idea how to begin a research essay. If it wasn’t for visiting Library support I would never have learnt how to meet assessment criteria. I knew how to write, but I didn’t know the technicalities of academic language or culture. Where do you even learn that?

I read a study (White 2011) that looked at minority students’ resistance to participation: “Not knowing the kinds of discursive styles common to classroom discussions was a primary reason for these students’ reluctance to participate in their classes.”

The research showed that student’s lack of participation was partly due to a feeling of academic inferiority, and that the students in his study said the schools they went to failed to sufficiently prepare them for tertiary education or to give them sufficient language skills to compete with other students. More interestingly, the study showed that using academic language ‘was, to these minority students, tantamount to “selling out” their cultural or ethnic traditions. To them, to be heard in class required “talking like white people, acting like white people”.’

In short: a lot of minority students’ issue with integrating into academic culture is the idea that they need to assimilate and take part in a culture that historically has been hostile toward them.

That study is talking about me, about many of my friends, about so many of us who are not white nor privileged, yet find ourselves negotiating a dominant white culture. It makes me think how much I have had to learn of whiteness and how much I have had to internalise in order to move forward in a society that rewards white academic discourse and practices. Fake it till you make it?

I guess hard work can get you far, but there are costs to upward mobility that not everyone can afford to pay.

I was privileged in that my parents have always had conversations with me about university and I could only ever imagine myself in that setting. Many of my friends took long breaks after enrolling in first year, some dropped out entirely, and some transferred to universities that were more multicultural in order to continue. The few of us who continued lost any sense of balance. We had a lot of catching up to do. We had to study and study and study to achieve the grades we thought we needed. And I knew that if I was to overcome the obstacles of race, gender and Islamophobia in applying for jobs, top grades would be my passport. As Islamophobia becomes more threatening in this country, many of us Muslims are becoming afraid that some of the privileges we possess are not enough and are not working for us any longer.

Now that I’m applying for jobs after a long maternity break, I’ve realised that privilege is also in your name, your networks, your resume. I know now upward mobility isn’t just good grades and skill. And I think about this as I’m beginning my path towards PhD; a PhD that most people tell me is going to be grilling and not worth much. I still won’t be looked at as an expert in my field of study. I’m still going to be competing for grants and positions against people who have the same qualifications as me, and everything more.

So why do it? I don’t have any answers to this. I can only listen to those who have already walked this path and can look at it from the other side. I see the path of learning as often quite personal and spiritual rather than seeing it in pragmatic terms. I think it’s important to know how upward mobility works, because no matter how we think we can acquire privilege, oppression and exclusion are more complex where the invisible barriers are very rigid.

And what does one person acquiring privilege do for the other marginalised groups? How are we sold this model for reform? I will only teach my children that superiority is unjust. Instead of wanting to move to a country or find a way to become amongst a supposedly superior or more privileged group, I will teach them to work towards undermining this construct of superiority.

Now that I know what privilege is, I see it everywhere. I didn’t know I was racially, economically, socially underprivileged as a child, but apparently I was. When we see our own children in this context we can begin to think of ways to build their resilience, knowing what they will face. But we eventually have to challenge, rather than maintain, the structures that give privilege to their peers. They’re our children, after all, and they are not inferior to anyone. It should be a privilege to know them.

References:

White, J. W. (2011). Resistance to classroom participation: Minority students, academic discourse, cultural conflicts, and issues of representation in whole class discussions. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 10(4), 250-265.

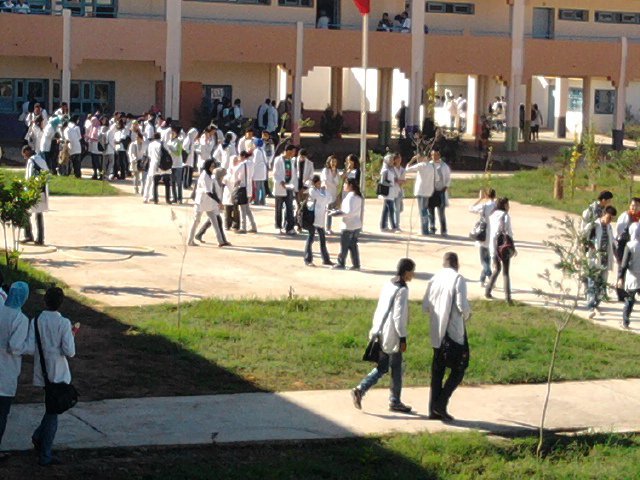

Cover image © At oussama (Own work), via Wikimedia Commons

About the author

Tasnim Sammak is a PhD student at the Faculty of Education, Monash University (Clayton). She's a spokesperson and founder of Solidarity for Palestine - Narrm, Melb.